Scientists from Germany, Italy and Saudi-Arabia have recently spent a week in Bremen to open and examine sediment cores from the Red Sea. The geologists and sedimentologists from the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT), the Institute of Marine Sciences (ISMAR-CNR) in Italy, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi-Arabia and the University of Göttingen worked closely together with the MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen using its laboratories for their work.

Image Gallery "Sampling of Sediment Cores from the Red Sea"

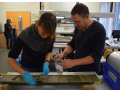

ZMT-Doktorand Yannis Kappelmann (AG Geoökologie & Karbonatsedimentologie) transportirt den Sedimentkern nach draußen zur Sägemaschine / ZMT doctoral candidate Yannis Kappelmann (WG Geoecology and Carbonate Sedimentology) takes the sediment core outside to the sawing machine | © A. Daschner, ZMT

Geologists call such an event a “sampling party”. Of course, there are no balloons or beer at this get-together but the excitement felt at such an occasion is akin to a party atmosphere. It is, after all, the very first time that the scientists are able to take a look inside their fruits of labour from the research cruise M193 on board the RV Meteor.

More than 84 metres of gravity cores were recovered during last autumn’s month-long expedition which took the scientists and crew across the Red Sea – from the port of Limassol in Cyprus to the port of Jeddah (Saudi-Arabia). The research cruise was led by chief scientist Thomas Lüdmann from the University of Hamburg.

Over the course of the “Replenish” expedition (Red Sea Paleoenvironmental Evolution under Monsoon fluctuations in the Pleistocene to Holocene) the researchers employed MARUM’s gravity corer to extract sediment from a depth of between 450 and 2,200 meters. Furthermore, a seismic survey of the ocean floor revealed the sea-floor structure, and MARUM’s remotely operated vehicle ROV MARUM-SQUID was deployed to study deep water corals and the mesophotic fauna.

Start of on-shore phase of M193 Red Sea exibition

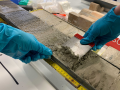

Now, the first part of the expedition’s on-shore phase has started with the sampling party when the so-called core flow is being established. First, each sediment core is cut in two halves (demonstrated in the photos by ZMT doctoral candidate Yannis Kappelmann). One half of the core is then photographed, scanned for elemental composition, the sedimentary layers and grains described in detail, and archived. The other half is sampled for laboratory analyses by the science team.

„We are opening all the cores and describe the sedimentary layers including the remains of organisms and volcanic particles we can see with the naked eye or through a magnifying glass,“ explains Hildegard Westphal, head of the working group Geoecology and Carbonate Sedimentology at ZMT and professor at University of Bremen. “Later on, we take more samples that the team will study in the labs to determine the biodiversity and geochemistry in more detail and to unravel climatic and ecological fluctuations.”

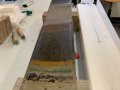

It is a laborious and often grubby task but with each opened core the excitement among the team grows. What secrets will the sediments reveal? To the untrained eye the cores mainly look like compressed greyish mud but every now and again there is a core with bright orange or red layers which even a layperson can distinguish.

Yet, for scientists the cores hold of a vast array of information including seawater properties such as salinity, temperature and chemical composition and evidence of the biological connectivity to the world ocean via the Bab al Mandab strait. Analysing this data, the scientists can learn more about the influence of glacial-interglacial sea-level changes and submarine volcanic activity on the Red Sea and its marine life in the past few hundred thousand years.

Salinity crisis in the Red Sea

“We want to find out how the biodiversity developed in the Red Sea, the youngest ocean on Earth with around 20 million years of age,” explains Hildegard Westphal. “The first corals started out around 16-18 million years ago followed by long periods of high salinity, a real salinity crisis, which repetitively and adversely affected marine life in the Red Sea since then. It was only in the era of the Pleistocene, especially in the interglacial periods, that coral started to flourish again.”

For most of its existence the Red Sea has been affected by increases in salinity, the ZMT geologist says. “When the sea level was higher in interglacial periods and the Red Sea was connected to the world ocean through the strait of Bab al-Mandab its marine life thrived. But when the sea level was lower and the Red Sea effectively cut off from the world ocean then salinity increased and living conditions became very tough for organisms,” Westphal adds. “Even today the Red Sea still has higher salinity and temperatures than the world oceans.”

The team led by Westphal is now eager to find out more about how organism diversity disappeared during limiting conditions due to high salinity and then re-established in periods of low salinity. For the researchers the sampling party at MARUM is only just the start of more exciting discoveries.